Recently, I have been at a loss for words. This is an exceedingly rare thing for me. Why have I been at a loss for words, you may ask. Because I have something of such life-changing importance to share with you, I have been paralyzed with fear I may not be able to express it in the manner it needs to be expressed.

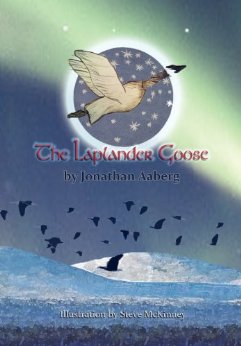

So I did what any smart feline would do, I asked someone else to find the words I could not find. And that person is my dearly beloved friend, Jonathan Aaberg. Jonathan is the author of the enchanting and moving book, The Laplander Goose,

which can be found on Amazon and elsewhere. I consider it a must read.

http://www.amazon.com/Laplander-Goose-Jonathan-Daniel-Aaberg/dp/0984736921

Here are the words Jonathan found that I could not find. Thank you, my dear friend.

Have you ever had a dream image that, within the dream, was amazing and revelatory, yet when you articulate it in waking life, sounds too simple? I recently had such a dream: I was walking on the long, familiar, carpet runner that pads a hallway in my home. I saw a bit of the corner upturned. I lifted it, and I saw on the other side of the rug the threads and remnants of what was once clearly a magnificent and gorgeous tapestry (maybe a magic carpet). I wondered, “How could I have not known this was on the underside of this runner?”

On waking I immediately felt I knew what this meant. I grew up in the Minnesota River Valley. That small river valley was the last home in Minnesota of the Dakota (sometimes called Sioux) Indians. For perhaps a thousand years, 2/3 of present-day Minnesota was their home, but by the 1860s they were allowed only to live within that narrow 10-mile corridor along the Minnesota River. It’s a beautiful river valley, and I even remember now as children we’d sometimes claim to have found arrowheads. As children we may have sensed the history under the soil, but as adults that sense vanished and it became as if the Dakota were never there.

They were. They had a culture as rich and beautiful as any, and as imperfect as all. They were becoming outnumbered. They were deliberately deceived as a matter of policy. They were starving. There was food locked up in warehouses. They were told their children could eat grass or their own dung. They slaughtered people, some guilty, many innocent. They were slaughtered likewise, some guilty, many innocent. They were hunted. They were exiled from Minnesota. Until last year a law remained on the books in Minnesota calling for their extermination or banishment from the state. (Thank you Gov. Dayton for finally cutting that bit of ugliness out of the legal tapestry).

The Dakota war of 1862 lasted only a few months and resulted in the largest mass execution in US history (to date) which took place in the quiet river town of Mankato, Minnesota 150 years ago on the day after Christmas in 1862. It’s not a well-known war despite it’s significance. It forever changed the frontier and the plight of Native Americans. It was not well known because, if there were TV at the time, the Civil War would have been on all the channels. It was not President Lincoln’s finest hour. Although he managed to restrain the call for vengeance and reduce the execution list to 38 (from the 300 plus originally listed), it was by and large his patronage that put too many callous and criminal people in direct charge of Indian affairs in Minnesota, disrupting the longer-term relationships that had been evolving between Indians and Whites.

That was ugly. And that is a lot to sweep under the rug. I’m sorry to put such an ugly and fragmented display in front of you, but there’s a reason I did. It provides contrast. For it is in the face of all this ugliness, hurt, and pain (felt on both sides mind you, but now more visable in the face of the Dakota), it is in the face of all this historical terror, that the people in the movie are approaching, on horseback and foot, with humility and what pride remains (a strong combination), to ask a simple thing: forgiveness.

Shocking, no? They’re asking forgiveness!? I mean, the aftermath of the Dakota war has left them a people near collective death, and has left the “victors” the spoils of war that would have been unimaginable in 1862. And they’re asking our forgiveness?

Well, the answer lies a little deeper. It lies in their recognition that forgiveness is possibly the only way that we can begin to close this wound. And yes, they will ask for it first, and, yes, this implies we should ask for it in return. But also implies that, if we ask, they will give us this precious gift.

Some, perhaps many, will fear that this means money, and perhaps it should. But if we can dodge that giant dollar sign monster, that snake and its cynical venom, perhaps we can get to the more existential question, the deep reckoning with history and a mutual forgiveness that will allow exactly this healing, so desperately needed for both and all sides. And you know what? I was in Mankato at the ceremony on the day after Christmas, the commemoration of the 150 years, and I think it’s starting to work.

It’s really quite simple. Our brothers and sisters are in deep pain and perhaps near cultural death. We are living, but with a lot of guilt. They are offering a precious gift that can start to take that pain away from us. And we can return the favor. Forgive. Be forgiven. Heal. Shouldn’t we do that?

Please watch the movie.